- Home

- Organic Vegetable Garden

- Crop Rotation

Crop Rotation

It Ain't Fancy: My Crop Rotation

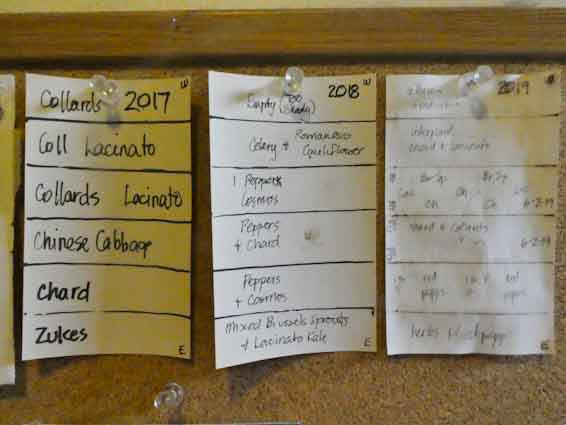

It Ain't Fancy: My Crop RotationPlan on 3x5 Cards

Crop rotation is the practice of growing specific crops in a different location each year. Ideally, that crop should not be grown on the same piece of ground for 2-6 years. Rotating crops to different places each year is a critical factor in keeping a garden fertile and healthy over time, and has been used by farmers and gardeners for centuries to maintain the fertility of their land.

The practice of letting land "lay fallow" (planting nothing in it) to let it rest for a year, used to be a part of crop rotation. But there are better alternatives for restoring fertility.

Planting a cover crop (particularly beans, peas, or annual grass) and then chopping and turning it back into the soil, returns nutrients and organic matter and boosts fertility better than a season of growing nothing. Growing a cover crop should be a part of every gardener’s rotation plan.

The Benefits of Crop Rotation

It prevents depletion of nutrients.

Different crops feed more or less heavily on certain nutrients. For example, cabbage family crops tend to feed heavily on calcium. If you always grow cabbage in the same location, they will remove a little more calcium from the soil every year, until eventually cabbage will no longer thrive in that same spot.

It minimizes disease and pest carryover from year-to-year.

For example, the cabbage root fly lays its eggs near the base of cabbage family plants, which then hatch into larva (cabbage root maggots) that burrow down and eat the roots. Eggs overwinter in the soil, just waiting for a yummy cabbage (or any other cabbage-family crop) to grow in the same spot. Too many years of the same crop in one spot can lead to “soil sickness”, a buildup of soil borne plant pests that can take many years to eradicate.

It improves soil structure.

By rotating crops that have deep root structures (like beets, whose feeder roots can go down 10 feet!) with shallower-rooted crops like cabbage, soil structure is enhanced. Deep rooted crops incorporate organic matter down deep and create freeways for earthworms and other microfauna to move about and do their important jobs.

It helps suppress weeds.

Big sprawly things like winter squash, pumpkins and potatoes have dense leaves that create an effective living mulch over the soil, which suppresses weeds. Vertical things like onions and carrots don’t do such a good job at this, so rotating tall-skinnies with dense-sprawlies can help reduce the amount of weeding you must do.

Before We Get to the Details...

If this is your first year gardening, you obviously don’t need to worry about rotating crops, but you can start preparing for future years by keeping a garden journal. Make a little map in your journal of what crops you planted where, so you can plan a different vegetable garden layout next year.

And if you are a seasoned gardener - if you haven’t been keeping a garden journal - start. You will find it an invaluable learning tool, as well being necessary to plant your crop rotations.

If you have a small garden, you will need to use a shorter rotation, like 2 years (meaning alternate years) because you don’t have so much space to play with. If you have a larger garden, you have the capacity to rotate on a longer schedule like 6 years, because you have more space to rotate through.

If you have had a bad outbreak of a particular pest or disease (for example, tomato fusarium wilt) try to avoid growing the affected crop in the same place for as long as you can, even if you have a small garden and have limited choices of where to plant things.

Planning this all out can become a confusing puzzle pretty quickly because there are so many variables to consider. Keep in mind at the beginning that gardening is an art as well as a science, and at some point you have to just give it your best shot and then surrender to nature.

There are two main things to think about when you plan your crop rotations, as well as several lesser ones.

Crop Rotation by Plant Family

In the big picture, crop rotation is more about plant families than about individual crops. Plants in the same family are generally susceptible to the same pests and often (but not always) have similar nutrient requirements.

One way to simplify crop rotation is to group your crops together by family. You can grow one family of plants in each bed, and then each year just rotate the different plant families through the different beds you have. Here is a list of common vegetable plant families:

Cabbage Family (Brassicaceae - also known as “Cole Crops”)

broccoli, brussel sprouts, cabbage, cauliflower, collards, kale, kholrabi, mustard greens, radish, rutabaga, turnip

Carrot Family (Apiaceae - formerly “Umbelliferae”)

celery, carrot, chervil, cilantro, dill, fennel, parsley, parsnip

Composite or Daisy Family (Compositae - formerly “Asteraceae”)

artichoke, arugula, chicory, endive, escarole, Jerusalem artichoke, lettuce, radicchio, sunflower

Goosefoot Family (Chenopodiaceae)

beet, spinach, swiss chard

Grass Family (Poaceae)

corn, wheat

Legume Family (Fabaceae)

beans, peas, lentils, peanuts; vetch and clover (cover crops)

Mint Family (Labiateae)

basil, mints, catnip, many herbs (all have square stems)

Nightshade Family (Solanaceae)

eggplant, pepper, potato, tomato, tomatillo

Onion Family (Alliaceae)

chives, garlic, leeks, onions, shallots (and asparagus - a different but closely-related family)

Squash Family (Cucurbitaceae)

cantaloupe, cucumber, gourds, melons, pumpkin, winter squash, zucchini

This sounds simple and forthright enough on paper, but in reality, you’ll probably find yourself having to mix things up a bit...

What if you only want to grow one crop out of a certain family, like carrots, and don’t want to grow an entire bed of it? What if you like to try growing some new things every year, that don’t fit into the rotation schedule you had planned? What if one of your beds is in partial shade, and the tomatoes won’t do well there? What if you had a bad tomato disease infestation one year, and need to take tomatoes off that particular bed for several years? And... where does companion planting fit in all this?

You can see how it can get complicated quickly.

Crop Rotation by Nutritional Need

Another way to practice crop rotation is to consider whether plants are heavy feeders, light feeders, or givers:

Heavy Feeders include lettuces, tomatoes, peppers, corn, Swiss chard, spinach and cabbage family crops (note these are all leaf and fruit crops)

Light feeders include carrots, turnips, radishes, beets (note these are all root crops)

Givers include beans, peas, cover crops like vetch or Austrian field pea (note these are all legumes)

To employ this method, plant heavy feeders in any given bed the first year, followed by light feeders the second year, and by givers (or a cover crop) in the third year.

But Wait... There’s More!

And it gets even more confusing: you will have to take into account your own garden’s peculiarities.

Where do you have shade? Where does it get extra hot near a wall? Where is the ground a bit soggy?

And what about companion planting? There are some plants that just seem to do better when grown near each other, such as carrots and tomatoes or collards and aromatic herbs. Now you truly have enough to make you crazy trying to figure it all out! (Someone should write a computer program!...).

What I Do In My Garden

The back half of two of my garden beds are in shade in the afternoon, so my tomatoes and peppers don’t like it there, but the cabbages and lettuces enjoy the protection from the afternoon heat. So I cannot make a simple choices to rotate plant families through all my garden beds, because some things won’t grow in every bed.

I try to plant crops in as mixed-up a way as possible, practicing the fine art of interplanting. “A little bit of this, and a little bit of that”. I do pay close attention to the light requirements of my plants and also give special notice to any spot where there was disease. I avoid growing anything from the affected family in that spot for several years.

I got powdery mildew last year on my zucchinis, so I planted lettuces in that spot this year, and I got fusarium wilt on my tomatoes, so I won’t be planting any tomatoes in that bed for the next 6 years.

I have marigolds scattered willy-nilly throughout the vegetables, and around the edges of the garden I have yarrow, borage, and aromatic herbs, which confuse pests and support beneficial insects.

I try to encourage as much biodiversity as I can, which mimics nature more closely and becomes sort of a real-time, immediate “crop rotation”. I don’t plant beans after corn, I plant beans with corn. And with cucumbers, and in amongst everything else.

The yarrow, borage, herbs, and even annual flowerpots near the vegetables provide a “flower insectary” that helps control some types of pests. I also provide the beneficial insects with a birdbath of water (filled with pebbles so they don’t drown) which they love to drink from. I know this isn’t part of “crop rotation”, but the whole wild thing sort of works together for the health of the garden.

I just do the best I can not to plant the same thing in the same spot two years in a row (or much longer if there has been disease), and once in awhile I plant a cover crop of Austrian field peas in an entire bed, to turn under and provide a bit of extra nitrogen. And of course I add compost like crazy.

It all seems to work!

Happy gardening everybody.

Help share the skills and spread the joy

of organic, nutrient-dense vegetable gardening, and please...

~ Like us on Facebook ~

Thank you... and have fun in your garden!

Affiliate Disclaimer

This website contains affiliate links to a few quality products I can genuinely recommend. I am here to serve you, not to sell you, and I do not write reviews for income or recommend anything I would not use myself. If you make a purchase using an affiliate link here, I may earn a commission but this will not affect your price. My participation in these programs allows me to earn money that helps support this site. If you have comments, questions or concerns about the affiliate or advertising programs, please Contact Me.Contact Us Page